Note

The following contains excerpts and diagrams from three great articles:

Imagine you want to use machine learning to suggest new bands to listen to. You could do this by having lots of people list their favorite bands and using them to train a model. The trained model might be quite useful and fun, but if someone pokes and prods at the model in just the right way, they could extract the music preferences of someone whose data was used to train the model. Other kinds of models are potentially vulnerable; credit card numbers have been pulled out of language models and actual faces reconstructed from image models.

Training with differential privacy limits the information about any one data point that is extractable but in some cases there’s an unexpected side-effect: reduced accuracy with underrepresented subgroups disparately impacted.

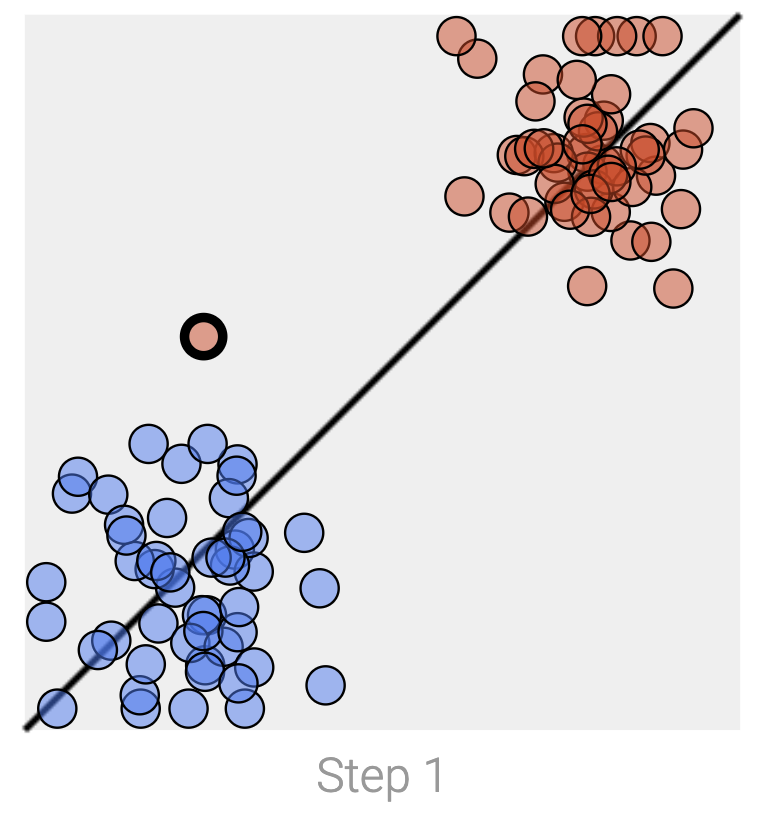

Recall that machine learning models are typically trained with gradient descent, a series of small steps taken to minimize an error function. To show how a model can leak its training data, we’ve trained two simple models to separate red and blue dots using two simple datasets that differ in one way: a single isolated data point in the upper left has been switched from red to blue.

We can prevent a single data point from drastically altering the model by adding two operations to each training step:¹

We can prevent a single data point from drastically altering the model by adding two operations to each training step:¹

- Clipping the gradient (here, limiting how much the boundary line can move with each step) to bound the maximum impact a single data point can have on the final model.

- Adding random noise to the gradient.

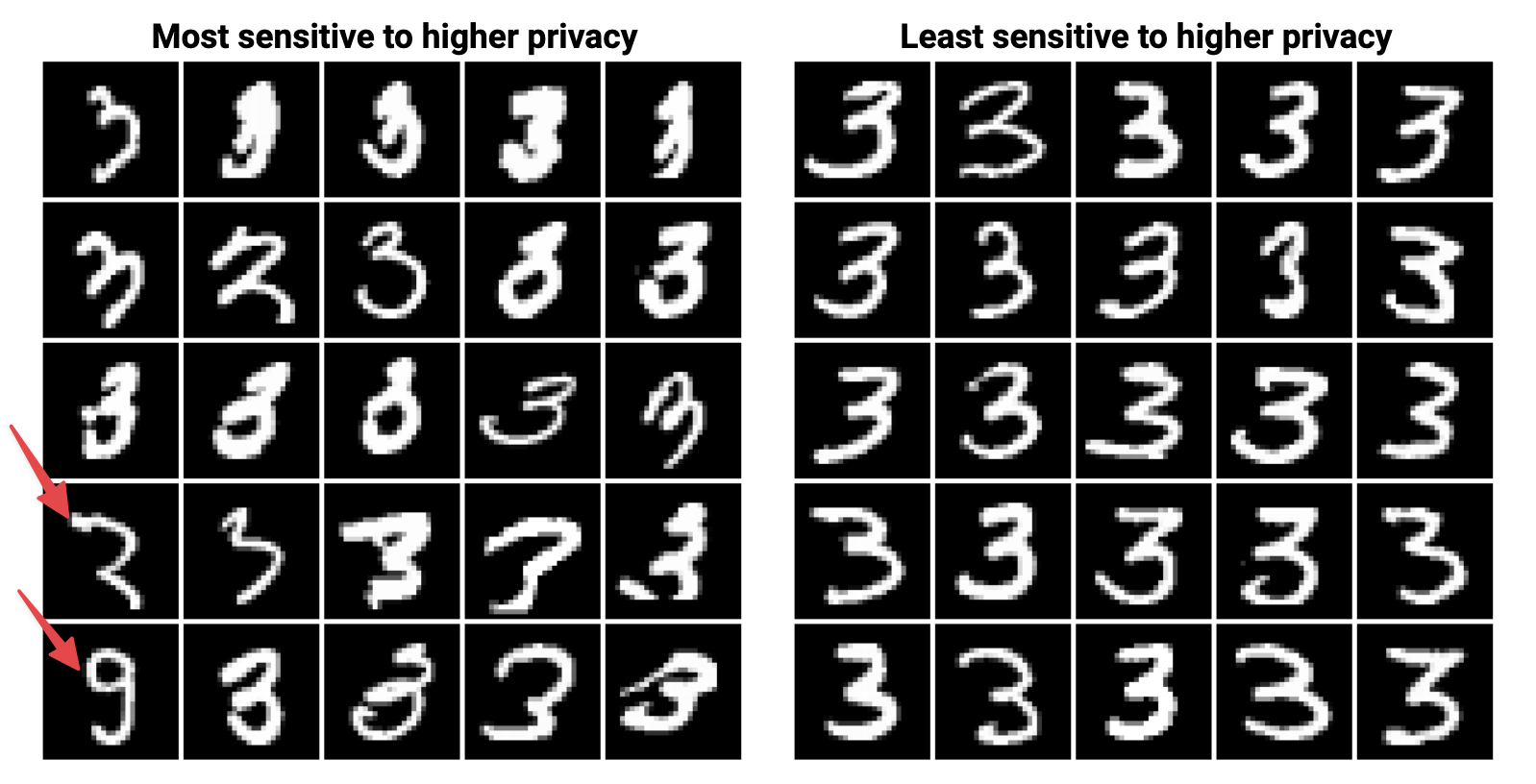

In Distribution Density, Tails, and Outliers in Machine Learning, a series of increasingly differentially private models were trained on MNIST digits. Every digit in the training set was ranked according to the highest level of privacy that correctly classified it.

On the lower left, you can see digits labeled as “3” in the training data that look more like a “2” and a “9”. They’re very different from the other “3”s in the training data so adding just a bit of privacy protection causes the model to no longer classify them as “3”. Under some specific circumstances, differential privacy can actually improve how well the model generalizes to data it wasn’t trained on by limiting the influence of spurious examples.

Increasing privacy can result in poor representation for minority classes

It’s possible to inadvertently train a model with good overall accuracy on a class but very low accuracy on a smaller group within the class.

This disparate impact doesn’t just happen in datasets of differently drawn digits: increased levels of differential privacy in a range of image and language models disproportionality decreased accuracy on underrepresented subgroups. And adding differential privacy to a medical model reduced the influence of Black patients’ data on the model while increasing the influence of white patients’ data.

Lowering the privacy level might not help non-majoritarian data points either – they’re the ones most susceptible to having their information exposed. Again, escaping the accuracy/privacy tradeoff requires collecting more data – this time from underrepresented subgroups.

ε-differential privacy

This is a great article.

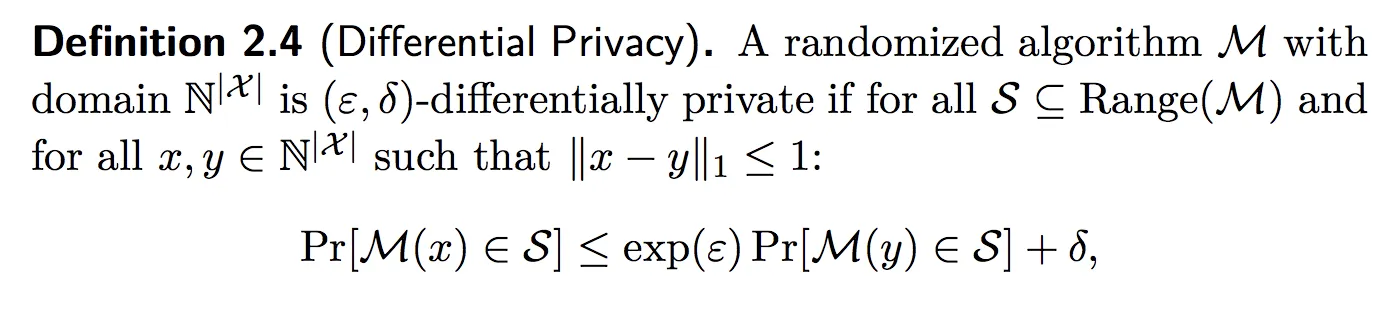

Formal Definition of Differential Privacy:

Where:

M: Randomized algorithm i.e

Where:

M: Randomized algorithm i.e query(db) + noise or query(db + noise).

S: All potential output of M that could be predicted.

x: Entries in the database. (i.e, N)

y: Entries in parallel database (i.e., N-1)

ε: The maximum distance between a query on database (x) and the same query on database (y).

δ: Probability of information accidentally being leaked.

Abstract differential privacy

- It gives the comparison between running a query M on database (x) and a parallel database (y) (One entry less than the original database).

- The measure by which these two probability of random distribution of full database(x) and the parallel database(y) can differ is given by Epsilon (ε) and delta (δ).

- Small values of ε require to provide very similar outputs when given similar inputs, and therefore provide higher levels of privacy; large values of ε allow less similarity in the outputs, and therefore provide less privacy.

differential privacy

This is a great article. “Pure” DP has a single parameter , and corresponds to a very stringent notion of DP:

An algorithm is if, for all neighboring inputs and all measurable .

By relaxing this a little, one obtains the standard definition of approximate DP, a.k.a. -DP:

An algorithm is if, for all neighbouring inputs and all measurable .

This definition is very useful, as in many settings achieving the stronger -DP guarantee (i.e., =0) is impossible, or comes at a very high utility cost. But how to interpret it? Most of the time, things are great, but with some small probability all hell breaks loose. For instance, the following algorithm is -DP:

- Get a sensitive database of records

- Select uniformly at random a fraction of the database ( records)

- Expose that subset of records publicly and delete all other records (all hell breaks loose for those exposed records💥)

This approach is since most of the time there is 0 probability of a record being exposed since it was deleted. However, there is a probability of a record being exposed.